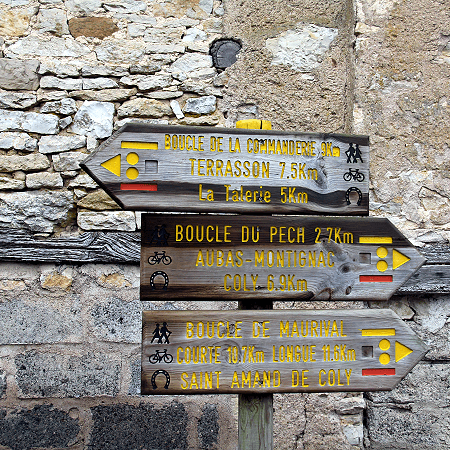

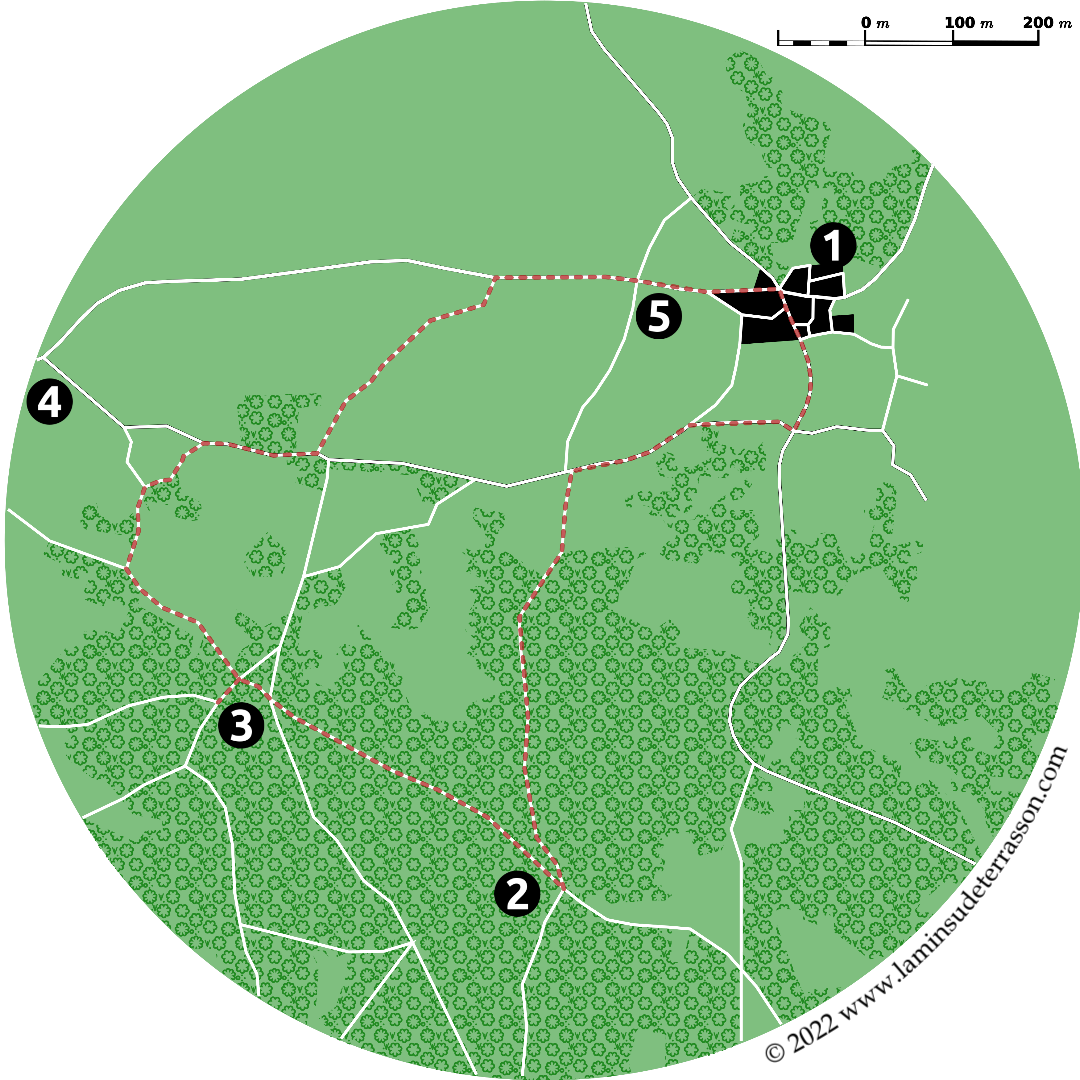

Coly valley hikes

J

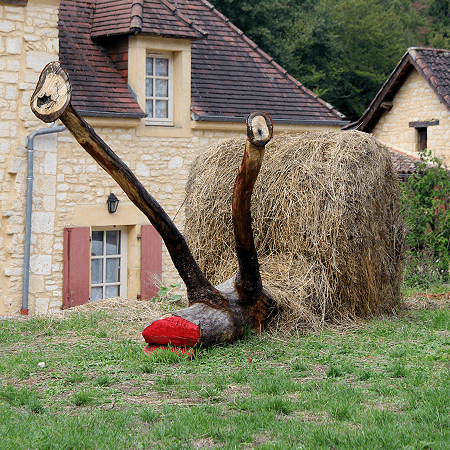

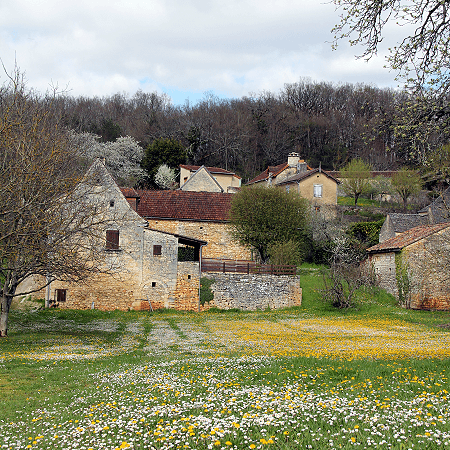

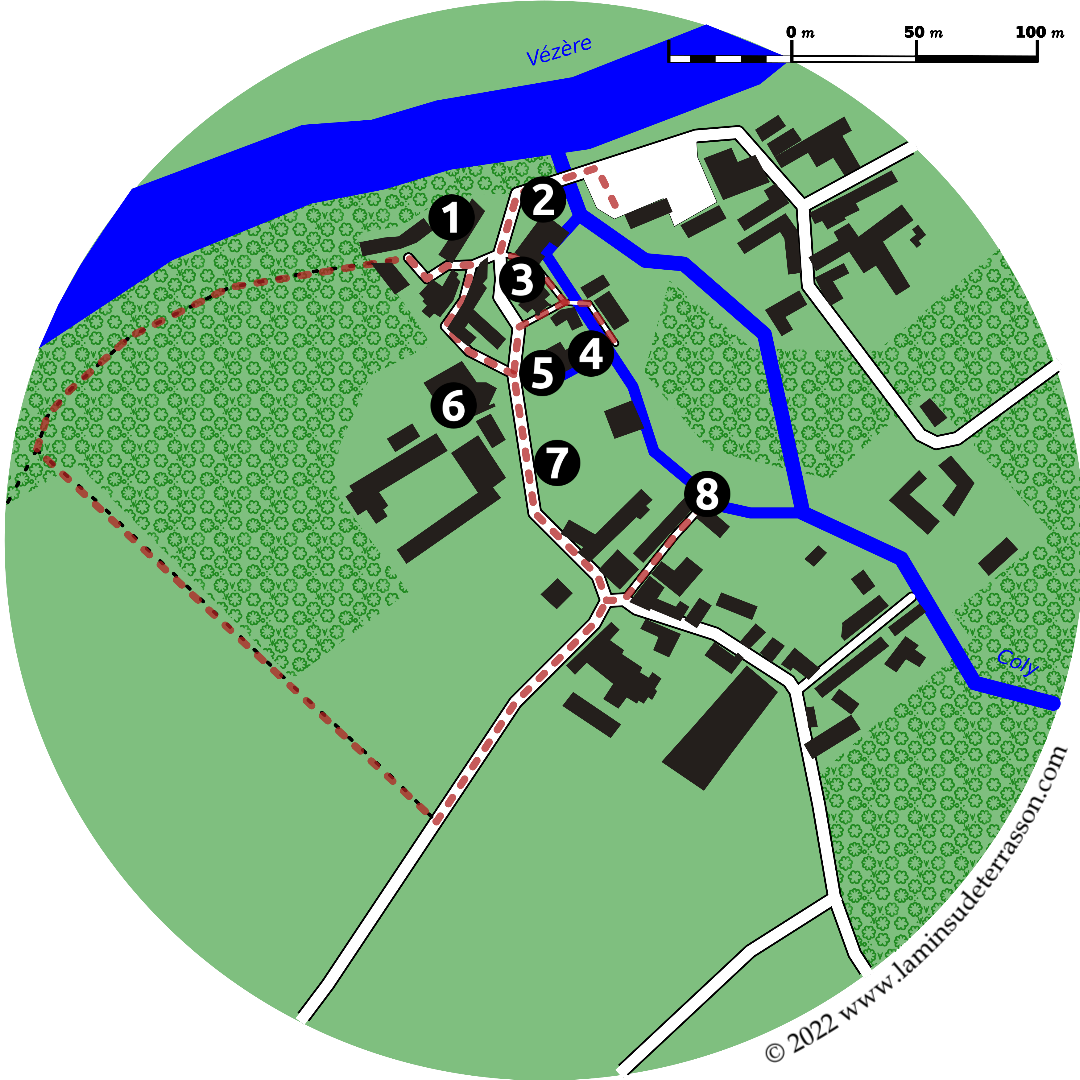

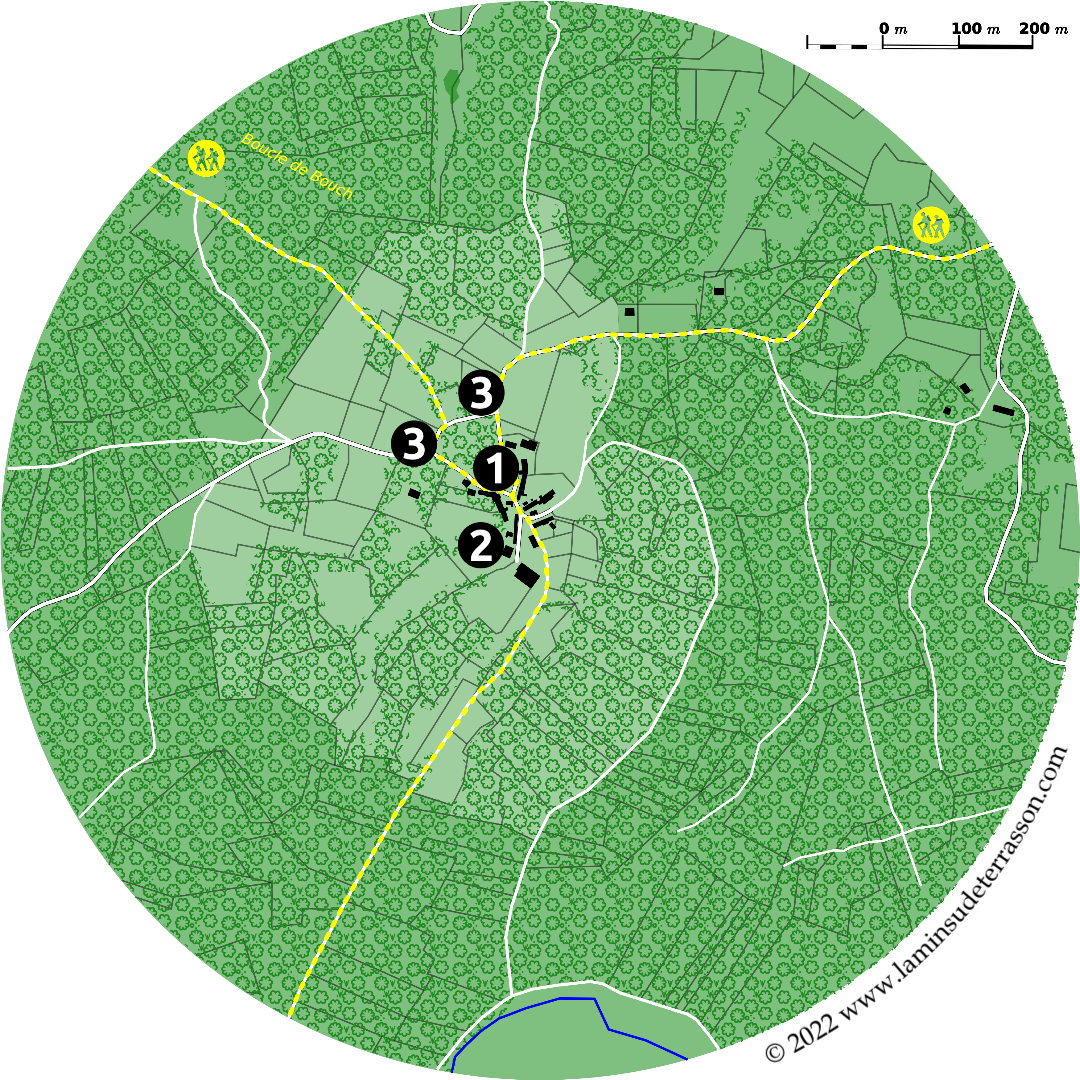

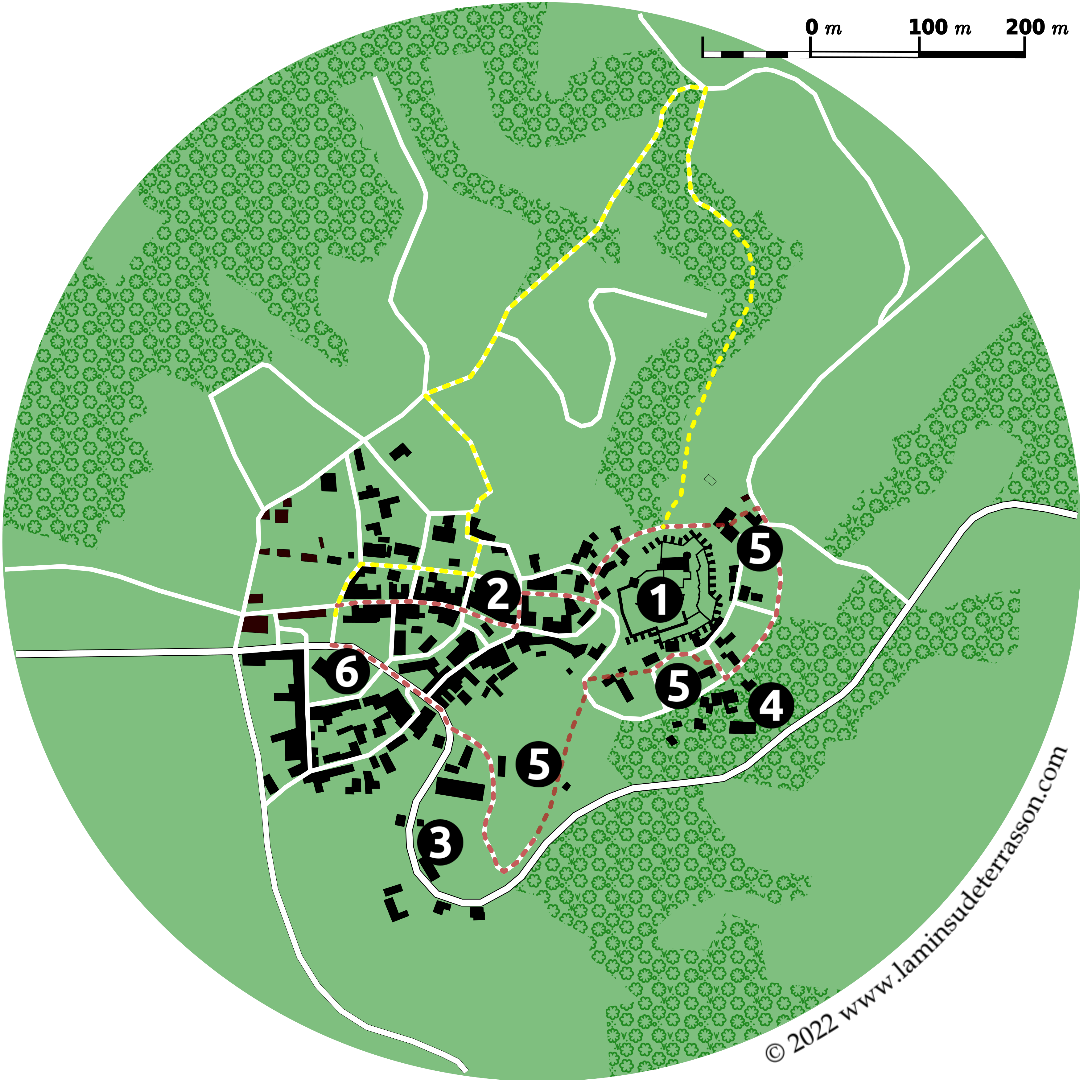

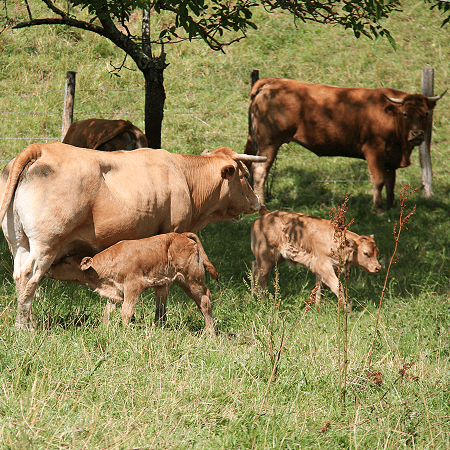

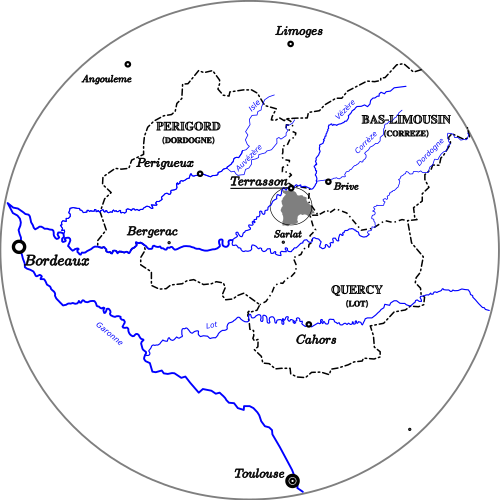

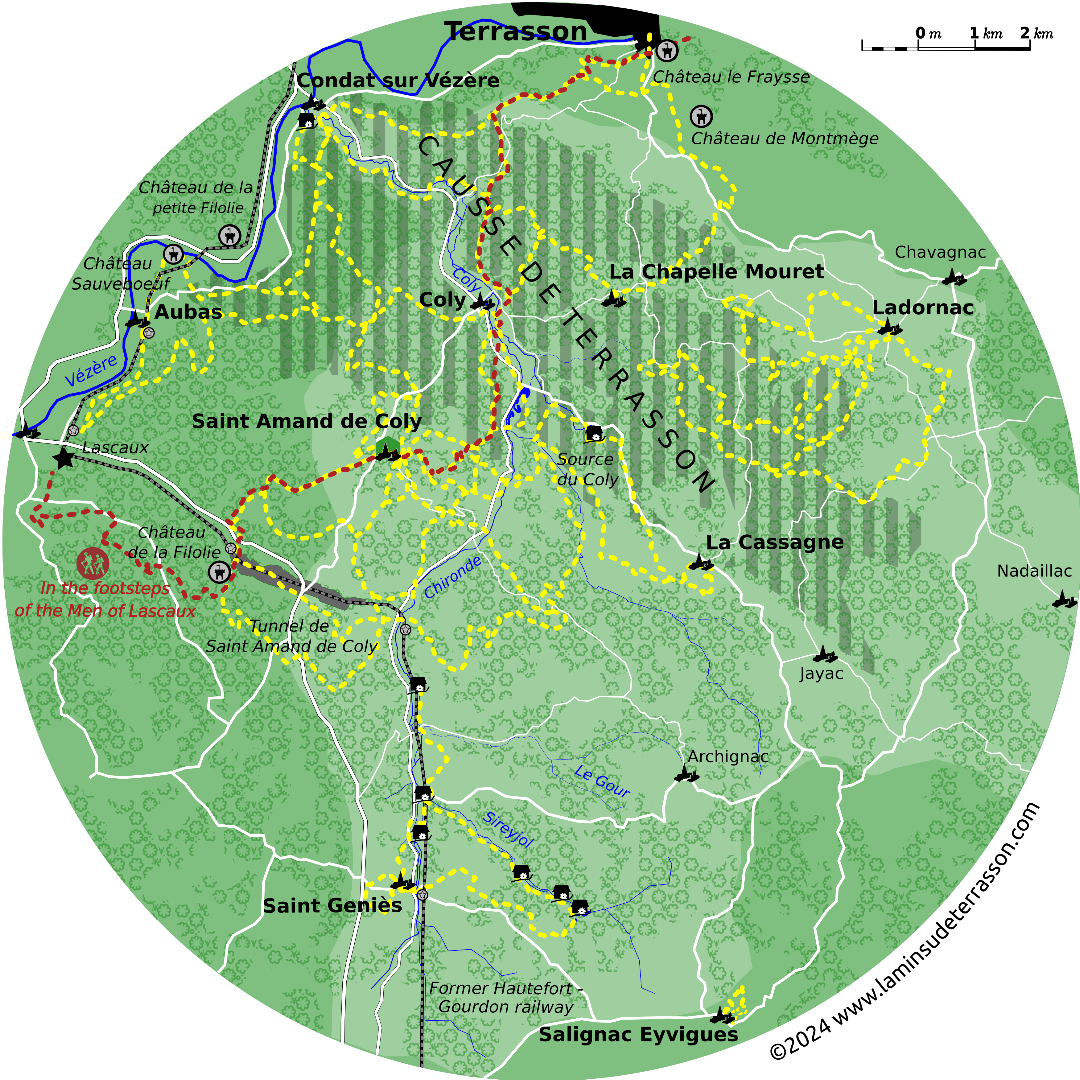

ust to the South of Terrasson, the Coly stream cuts through steep hills with a remarkable geology: Jurassic formations to the north and Cretaceous to the south. Small streams drain some 170 km2 of undulated forestland, scattered with rich agricultural valleys, grasslands, walnut groves, villages and small hamlets.

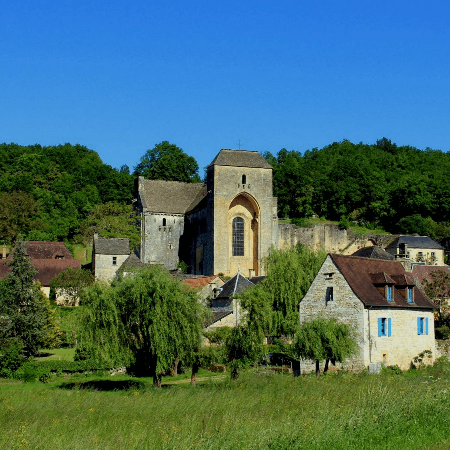

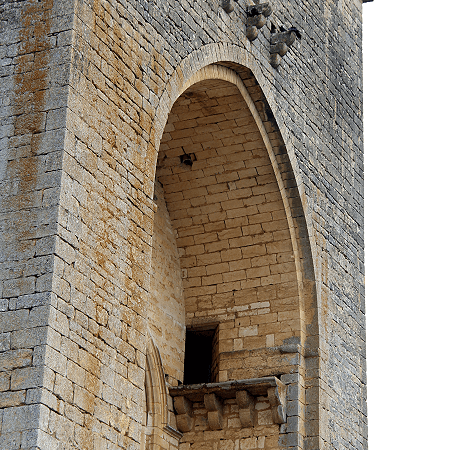

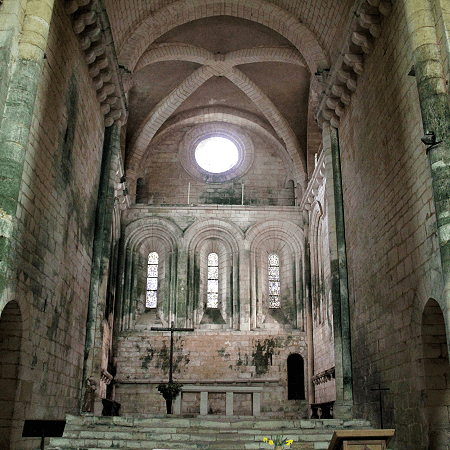

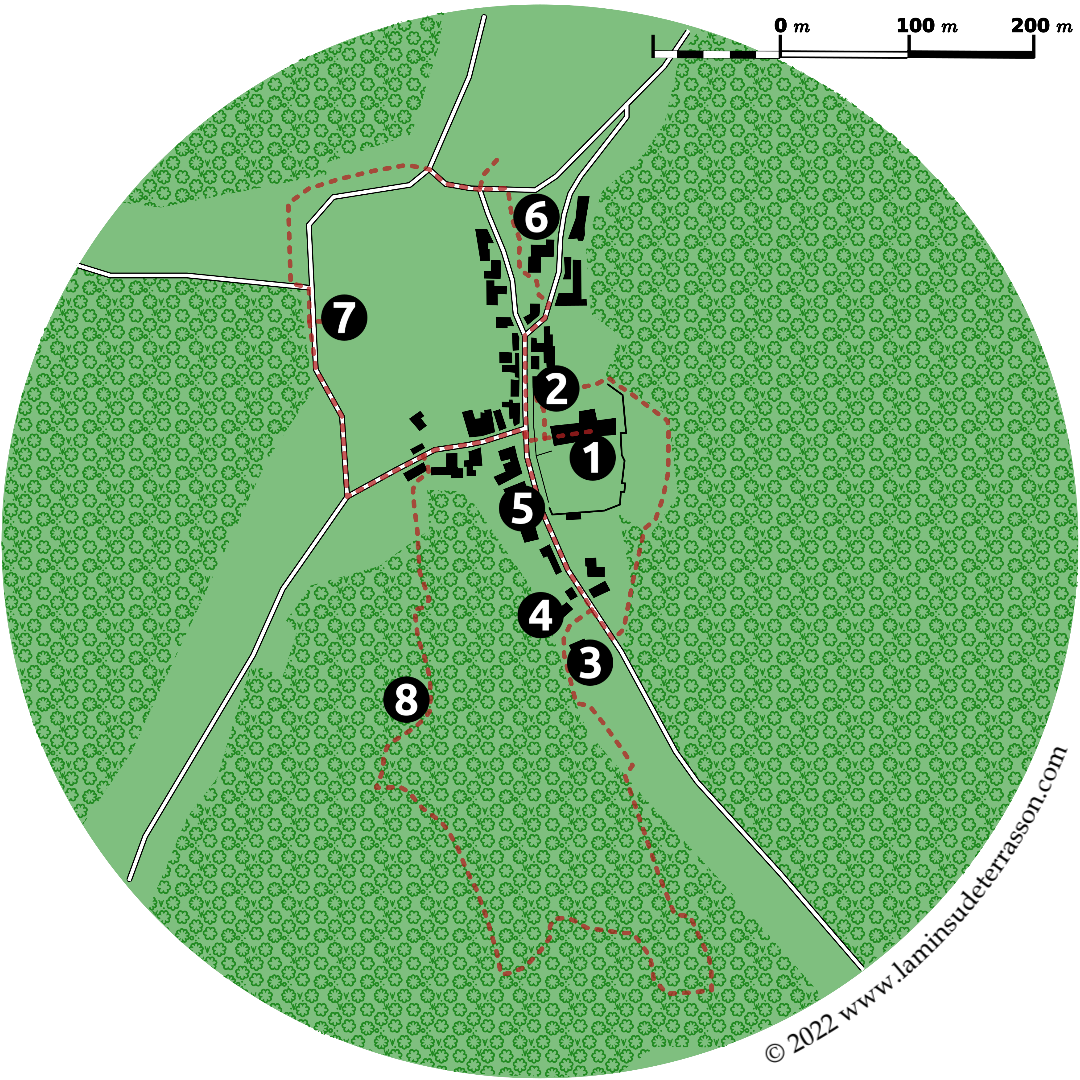

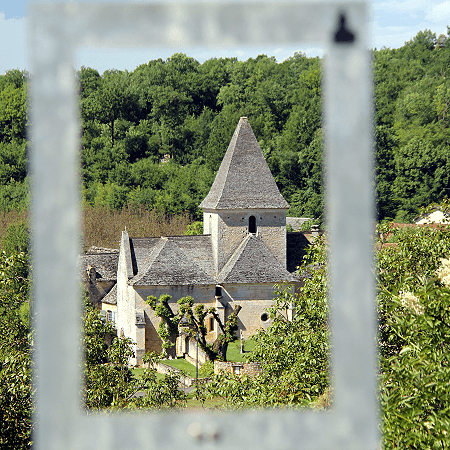

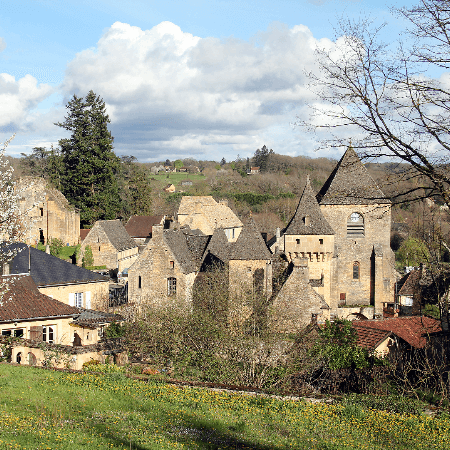

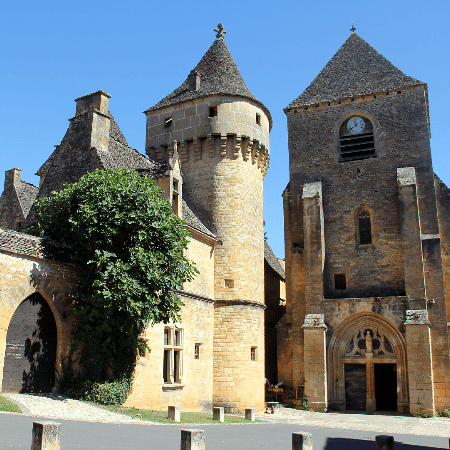

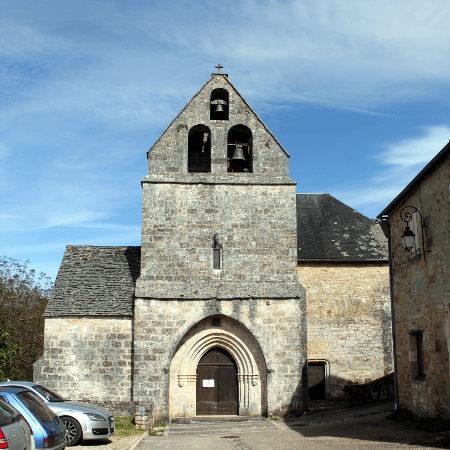

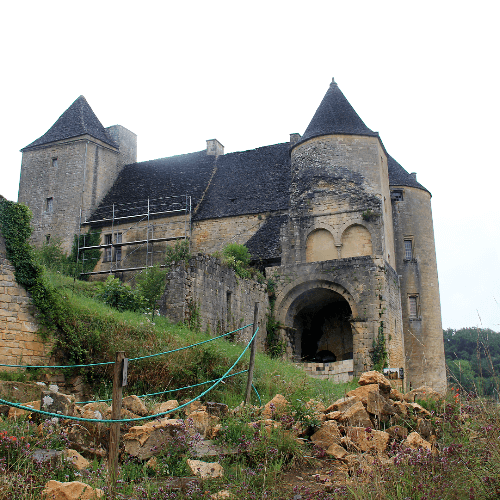

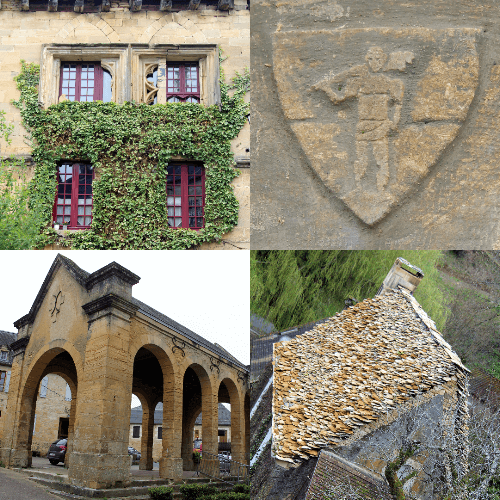

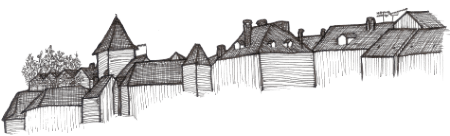

Including Saint Amand de Coly classified as one of France’s most beautiful villages and the hamlet of Chapelle Mouret protected Architectural, Urban and Landscape Heritage Protection Zone (ZPPAUP - Zone de Protection du Patrimoine Architectural, Urbain et Paysager).

Including Saint Amand de Coly classified as one of France’s most beautiful villages and the hamlet of Chapelle Mouret protected Architectural, Urban and Landscape Heritage Protection Zone (ZPPAUP - Zone de Protection du Patrimoine Architectural, Urbain et Paysager).

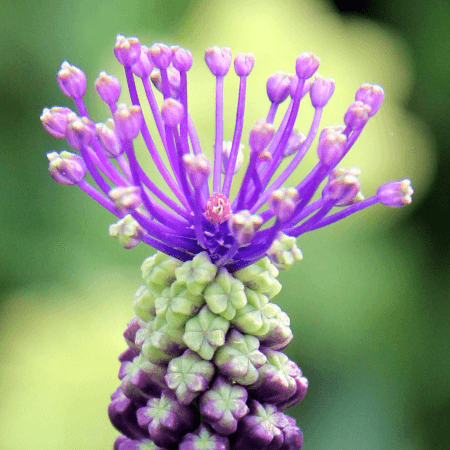

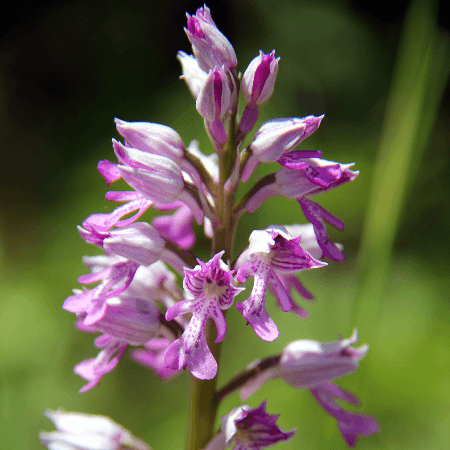

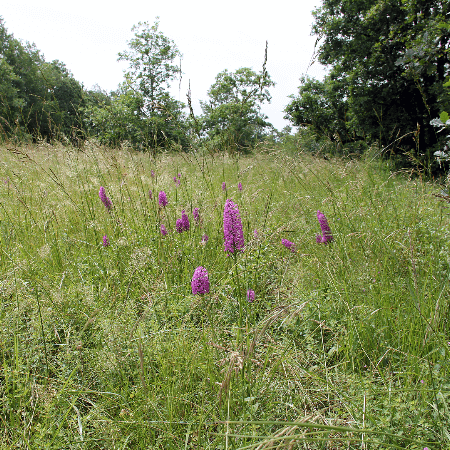

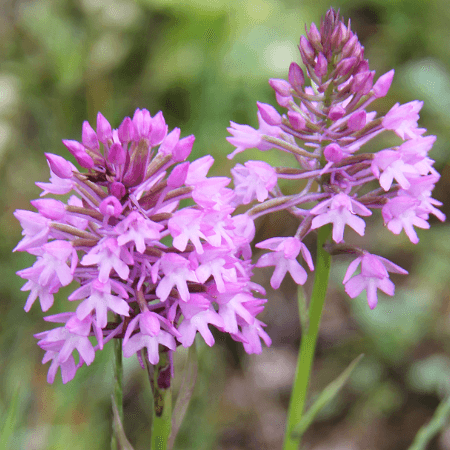

The Causse de Terrasson is a large natural area of ecological interest (ZNIEFF: Zone Naturelle d'Intérêt Ecologique, Faunistique et Floristique) encompassing representative environments of the Périgordian causses: to the north the hills are covered with a mosaic of pubescent oak forests, juniper heaths and lean grasslands. To the south forest of chestnuts and hornbeam.

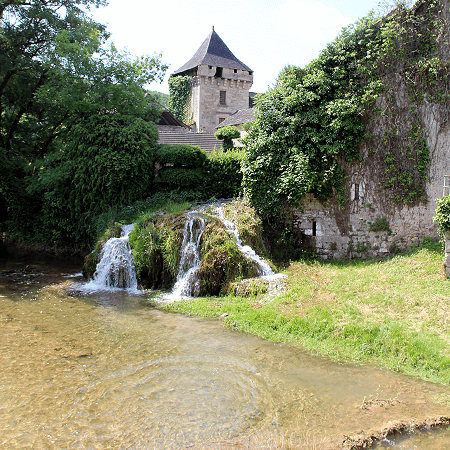

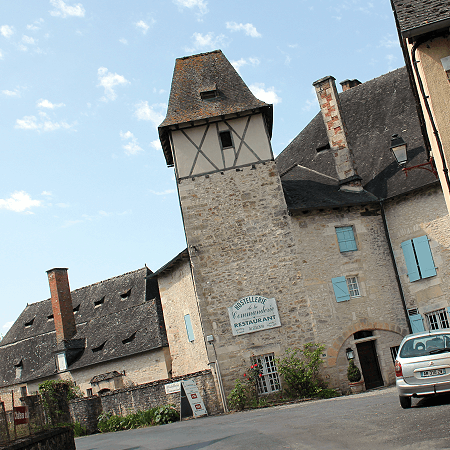

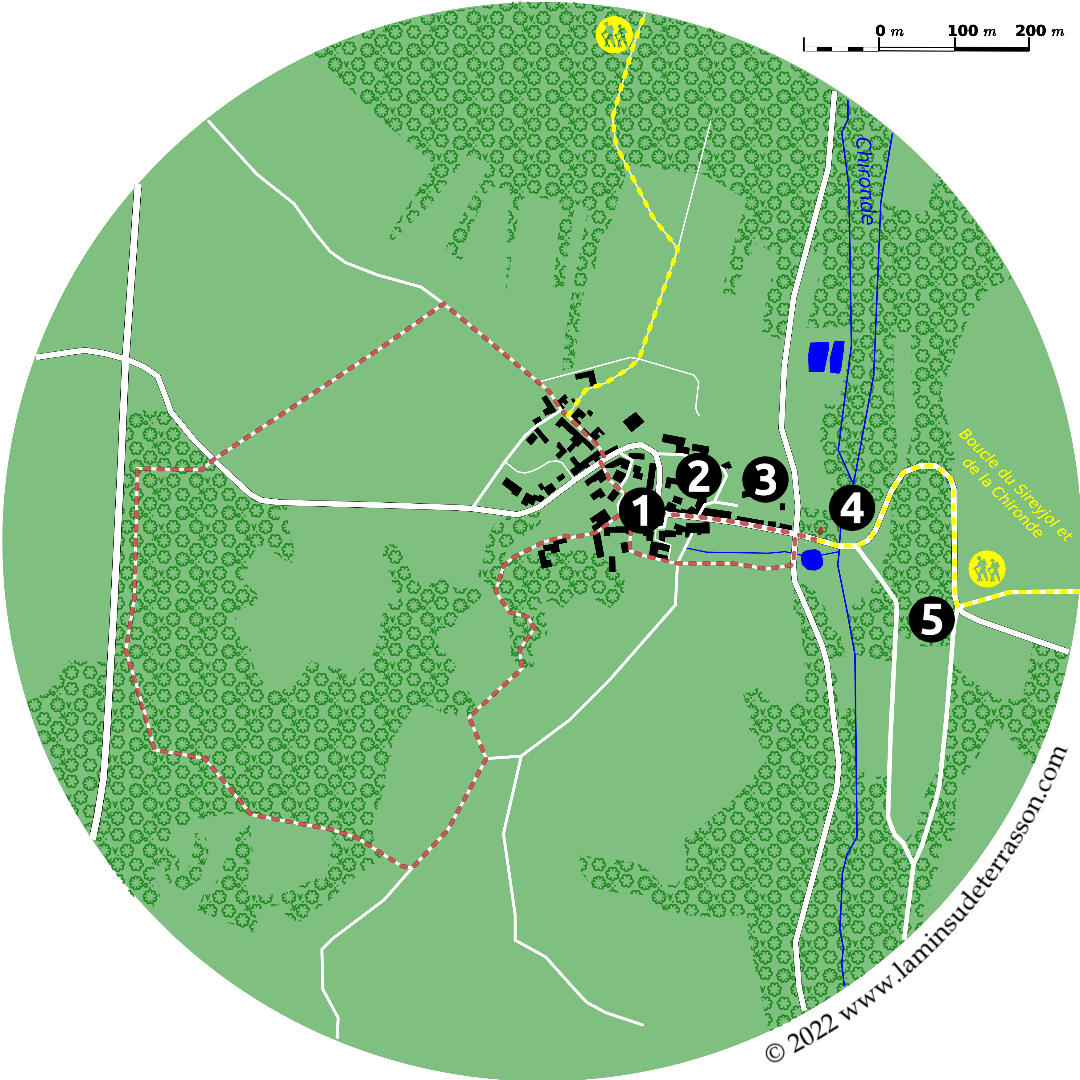

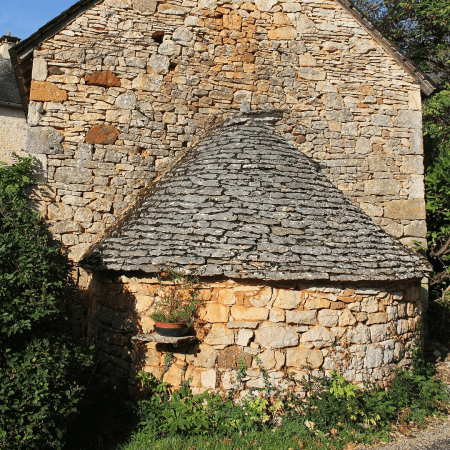

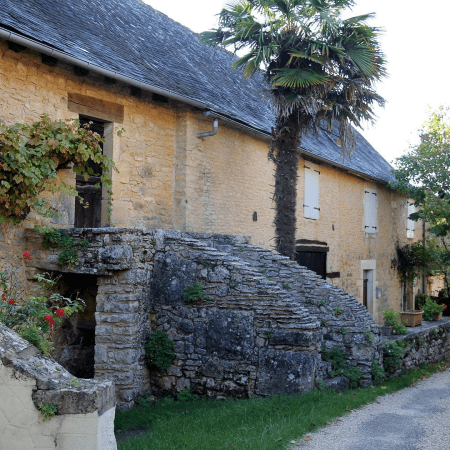

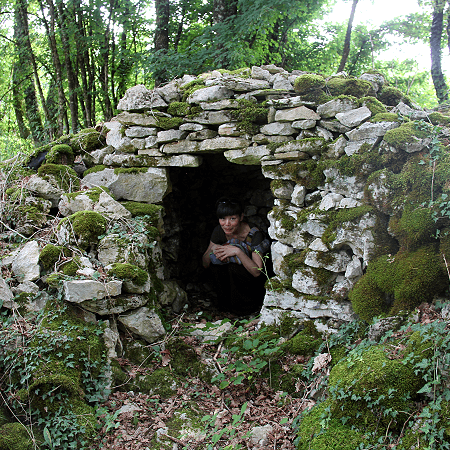

The Coly stream falls into the Vézère at Condat-sur-Vézère, once the principal seat of the Hospitallers with dependencies in La Cassagne and Ladornac. Upstream, the Chironde tributary supports a series of watermills, on its upper reaches the village of Saint Geniès with its remarkable concentration of vernacular architecture and its typical lauze (dry stacked natural stone) roofs.